A Wrong Turn in the Desert

By Osha Gray Davidson

Rolling Stone, 27 May 2004

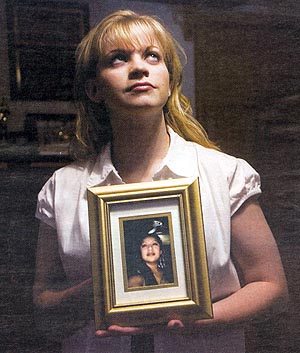

When Jessica Lynch’s convoy veered off course in Iraq, Private Lori Piestewa became the first Native American woman to die in combat on foreign soil. So why has the Hopi soldier been all but forgotten?

Nasiriyah, Iraq. 23 March 2003: 0600 hours

An hour before the ambush, Pfc. Lori Ann Piestewa knew something was wrong. It was just before dawn, only three days into the U.S. invasion of Iraq, and her unit’s slow-moving convoy was approaching a bridge over the Euphrates River. That’s when Piestewa saw it: the heavily fortified town of Nasiriyah, rising out of the sands like a mirage. She stared in disbelief through the dusty windshield of the Humvee she was driving. A city? Shouldn’t they be in the desert?

At the far end of the bridge, Piestewa spotted an Iraqi military checkpoint. She braced for the worst. But as the column lumbered by, the Iraqi soldiers inside waved, beckoning the Americans deeper into the city.

Piestewa turned to her best friend, Pfc. Jessica Lynch, who was riding in back of the Humvee. They were both thinking the same thing: We’re not supposed to be here.

It was a small error, but a fatal one. The 507th Army Maintenance Company – a support unit of clerks, repairmen and cooks – had taken a wrong turn in the desert, stumbling into Nasiriyah by mistake. Without warning, the company suddenly found itself surrounded, an easy target for Iraqi soldiers and fedayeen paramilitary forces armed with AK-47s, mortars and rocket-propelled grenades. The ensuing attack proved to be the Army’s bloodiest day of the ground war – and the first hint of the deadly quagmire that Iraq would soon become. Eleven American soldiers were killed and nine were wounded when the 507th came under what the military later described as a "torrent of fire" in Nasiriyah.

The attack made Jessica Lynch famous. U.S. Special Forces later plucked her from an Iraqi hospital and rushed her to safety, and the media seized on the daring rescue to create a tale of American heroism and valor. But the real story of what happened in Nasiriyah that day – and the clear warning it offered of things to come – involves a different soldier, one who gave her life to protect her friends. Lori Piestewa, born and raised a Hopi on the Navajo reservation in Arizona, became the first American woman to die in the war, and the first Native American woman ever to die in combat on foreign soil. Only twenty-three years old, Piestewa saw herself as a Hopi warrior, part of a centuries-old tradition developed by a people who once resisted an invasion and occupation by the U.S. military – much as the Iraqis are today. She went to war, but she believed above all in peace, in doing no harm to others. "I’m not trying to be a hero," she told a friend just before the invasion. "I just want to get through this crap and go home."

Her fellow soldiers remember her differently. When Jessica Lynch thanked a long list of people at her triumphant homecoming in West Virginia, she devoted her final words to Piestewa, her former roommate at Fort Bliss, Texas, where the two had been stationed before the war. "Most of all," Lynch said that day, "I miss Lori."

Since the attack, Lynch has insisted again and again that she was not a hero, that she was only a survivor. Asked who was a hero that day in Nasiriyah, she doesn’t hesitate. "Lori," she says firmly. "Lori is the real hero."

The high desert country around Tuba City, Arizona, where Lori Piestewa grew up, looks a lot like southern Iraq. Vast, open stretches dominate the barren landscape, punctuated now and then by red sandstone mesas. As a child, Lori spent weekends racing her three-wheeled ATV across the sand dunes north of town. Only six inches of rain fall here each year – about the same as in Nasiriyah. When the producers of Three Kings, the George Clooney movie about the first Gulf War, were looking for a stand-in for Iraq, they decided to film in the Arizona desert.

If Lori had been born a century earlier, the United States government would have considered her an enemy. In the late 1800s, the U.S. Cavalry invaded Hopi lands and decreed that the fields now belonged to white settlers. The Hopi fought back, not with guns or arrows, but with nonviolent resistance. (The name Hopi means "Peaceful People.") In defiance of the military, Hopi farmers continued to cultivate their lands. The Army arrested nineteen Hopi leaders and sent them to Alcatraz, where some spent as long as two years in solitary.

Piestewa was raised in this Hopi tradition of nonviolence, which emphasizes helping others, starting at home, with one’s own family and clan, and extending outward to include the entire community and nation. (Her father, Terry, is Hopi; her mother is Hispanic.) As a baby, Lori had her hair washed in a Hopi ceremony and was given the name Köcha-Hon-Mana, White Bear Girl. "We Hopi were put on this earth to be peaceful," explains Terry, a short, round man with graying hair and a soft voice.

Terry Piestewa fought in Vietnam, but it’s not something he is proud of. He was drafted and didn’t want to go to prison like two of his brothers-in-law who had refused to fight in Korea. Asked about his tour of duty, he folds his arms across his chest and his eyes fill with tears.

"A lot of us that did do harm, we have that on our conscience," he says. "It’s going to stay, and there’s nothing that can take that away."

Camp Virginia, Kuwait. 20 March: 1400 hours

Sixty-four members of the 507th pulled out of camp at the tail end of a column of 600 vehicles. Piestewa was behind the wheel of a Humvee, the driver for the 507th’s senior noncommissioned officer, First Sgt. Robert Dowdy. They were headed to the south of Baghdad to support a Patriot-missile battalion. The goal was to take the Iraqi capital as quickly as possible. Speed wasn’t just essential to the plan. Speed was the plan. As Gen. Tommy Franks, the man in charge of the assault, liked to say, "Speed kills."

But as the vehicles raced across the open desert, the 507th lagged behind. Tires on the heavy trucks spun uselessly in the fine sand until their axles reached the ground. Mired vehicles had to be pulled out; broken trucks were repaired on the spot or towed. It was the essence of grunt work – nothing heroic, just necessary.

At one point, Lynch’s five-ton truck, hauling a "water buffalo" – a trailer filled with 400 gallons of water – broke down. She was standing in the desert, frightened and bewildered, when a Humvee rattled over.

Piestewa – known as "Pi" to her fellow soldiers – looked at her shaken friend. "Get in, roommate," she said.

Maybe watching all those Westerns with people getting scalped makes people think that’s what a warrior is," says Lori’s oldest brother, Wayland. But for Hopis, he says, being a warrior has nothing to do with hurting people. "My sister is a warrior because she did the right thing, the honorable thing: going to Iraq when she didn’t have to, because she felt it was the ethical and moral thing to do. That’s what being a warrior is about: doing what’s right, even when it’s difficult and means sacrifice."

Lori never shied away from doing what was difficult. "She was really strong-willed," says her brother Adam. "We were always telling her not to do things, and she’d just go ahead and do them." The boys of Tuba City learned that if they were going to get in White Bear Girl’s face, they’d better be prepared to fight. Lori was small for her age – she would top out at five foot three – but even the bigger boys were intimidated by her. "She never backed down," says Adam. "She was never afraid to take on anybody."

Most of the time, though, Lori used those same traits in the Hopi way: to help whatever group she was part of. When she was eight years old, she played shortstop for the local Little League team. On the day before a championship game, the coach was hitting practice grounders when one ricocheted off the iron-hard dirt and struck Lori full in the face, breaking her nose. Despite two blackened eyes that made her look like a panda, she insisted on playing the next day. The team was counting on her, she argued. Her family gave in. With Lori at shortstop, the team won the championship.

"She couldn’t not play," says Adam. This wasn’t about choice – it was about duty.

Southeastern Iraq. 21 March: 2200 hours

By nightfall, the 507th had fragmented into two groups. The lighter and faster-moving vehicles led by Capt. Troy King, the commanding officer, continued on to the next position – code-named Lizard. The heavy trucks, some now in tow, were hours behind. Piestewa’s Humvee was designed for this terrain. But Dowdy was responsible for making sure the stragglers got to Lizard safely, so their Humvee didn’t reach the position until late afternoon.

Only King and his driver were waiting for them. The main convoy, and the rest of the 507th, had left two hours earlier. The supply company was now at half-strength, deep in hostile territory, without the protection of the forward battalion.

King organized a miniconvoy, with his vehicle in the lead and Piestewa driving Dowdy near the rear. Just after sunset, thirty-three soldiers in sixteen vehicles set off for Highway 8. Piestewa was exhausted. They all were. None of them had slept in thirty-six hours, time they had spent doing grueling physical labor. Trying to catch up to the main convoy, King attempted a shortcut across the desert. It got bad fast. After a few hundred yards, a truck would bog down in sand. They’d pull the vehicle out, repair it and start up again – until another truck got stuck and the process began all over again. They reached Highway 8 at 12:30 a.m., March 23rd. It had taken five hours to travel nine miles.

But now they were on a highway, code-named Route Blue, and made good time. In a half-hour they reached the intersection with Route Jackson, their intended route. For reasons still not fully understood, King mistakenly believed he was supposed to continue on Route Blue. The military had established a checkpoint at the intersection to prevent any mistakes. But the main convoy had passed by hours before and the checkpoint was all but deserted. Instead of turning left on Route Jackson, King led the 507th north on Route Blue – directly toward the city of Nasiriyah.

Lori joined just about every sports team there was in Tuba City – which says as much about the lack of things to do in Tuba City as it does about her love of athletics. The town’s unemployment rate rarely dips below twenty percent, and nearly one in four families lives in poverty – three times the national average. On cold mornings, smoke curls from the chimneys of hogans and ramshackle trailers. Broken-down cars adorn dusty yards, stray dogs with washboard ribs prowl unpaved streets, and a guy with beer breath hustles quarters outside McDonald’s at ten o’clock on Sunday morning. The closest movie theater is in Flagstaff, seventy-five miles away. Ask local kids what they think of the town, and you’re likely to get a two-word reply: "It sucks."

Like most other kids in Tuba City, Lori felt the push of a stunted economy and the pull of other places. In high school, eager for new experiences, she joined the Junior Reserve Officer Training Program. No one was surprised when she became the commander. She was no gung-ho super patriot, but she loved the physical challenges and the camaraderie. As a junior, her unit was scheduled to attend its first-ever statewide finals, taking part in a physical-fitness competition. The day before the event, Lori dislocated her shoulder in practice. Determined not to let her comrades down, she managed to do more chin-ups than any other woman, winning the women’s overall competition.

By the beginning of her senior year, Lori was looking beyond high school. Neither of her parents went to college – her mother is a secretary and her father does maintenance in the local schools – but Lori wanted that degree. She was looking at different colleges when she ran into another obstacle. She discovered she was pregnant.

There aren’t many job options on the reservation, and even fewer for girls who are poor, pregnant and seventeen. College was put on hold. Lori married her boyfriend and had two children, but the marriage fell apart. She wound up living with her parents in the small but comfortable trailer where she was raised, feeling trapped and desperate. She hated taking things for free, even from her family. So she left her kids in the care of her folks and enlisted in the Army.

For Native Americans, patriotism and military service are complex, often contentious issues. Some Indians call those who join the military "apples" – red on the outside, white on the inside. (One T-shirt popular on reservations bears an old-time photograph of four Indians, rifles at the ready, with the words, HOMELAND SECURITY: FIGHTING TERRORISM SINCE 1492.) But many American Indians still consider this their homeland and have fought to defend it; during World War II, one in eight Indians joined the military.

For Lori, the military was just another way to help others – starting with her kids and her family. "She wanted to fend for her children," says her mother, Percy. "She was going to build us a house and take care of us. I think she weighed the options that she had. We’re not rich enough to send her to college. When you have obstacles in your way, you take what life offers."

If there was one thing Lori knew, it was how to deal with obstacles. In April 2001, with just two weeks to go in basic training, she broke her foot during a training exercise. She kept the injury quiet. "She didn’t want to get held back," her dad recalls. Lori simply bandaged her foot and continued the punishing training as if nothing were wrong. After her graduation ceremony, Lori couldn’t wait to remove her shoe. Even her parents, long accustomed to her injuries, winced when they saw her grotesquely swollen and bruised foot.

Outskirts of Nasiriyah. 23 March: 0600 hours

Dawn has special significance for the Hopis, who consider the sun the creator. Piestewa saw it rising out of the desert as she followed the convoy off Route Blue and onto a smaller road. King – now without sleep for fifty hours – had missed a left turn that took Route Blue just west of the city. The smaller road, flanked by partially drained marshes, plunged into the eastern section of Nasiriyah. The town was just waking up. Men with AKs slung over their shoulder gawked at the Americans; pickups mounted with large-caliber machine guns drove slowly by. The potential for violence crackled in the morning air. With its narrow streets hemmed in by low buildings of mud and concrete, Nasiriyah would be a hellish place to come under fire.

The Americans felt a surge of relief as they crossed a canal marking the other side of Nasiriyah. A mile later, King checked his global-positioning system and realized for the first time that he was in the wrong place. They were too far east. There was only one way to get back on route – they had to retrace their path through Nasiriyah. King gave the order to "lock and load."

The convoy made the first turn around seven o’clock. King was in the lead; Piestewa brought up the rear. Suddenly, King’s driver, Pvt. Dale Nace, heard the popping of small-arms fire. "Trucks were hitting the gas and coming around the turn fast," he recalls. "They were trying to get away from something."

Several rounds slammed into the Humvee that Piestewa was driving. At least two bullets punched through her plastic side window, missing her head by inches.

In the confusion, King missed the turn that led back into the city. Dowdy yelled over his radio, alerting King to his mistake. Now they had to find someplace wide enough to turn the big trucks around. But the road was too narrow, and they kept driving, headed in the wrong direction. Under the strain, a five-ton truck broke down and had to be abandoned.

It was a harrowing two miles before the convoy managed to turn around and head back toward the city. King had completed the turn and was racing back west when he saw the Humvee driven by Piestewa bringing up the rear, still heading east. The two vehicles stopped. They weren’t taking fire at the moment, so King jumped out to confer with Dowdy, leaving Piestewa and Nace a couple of feet from each other in their Humvees.

"Pi, are you all right?" Nace asked. The two were friends and had worked in the same office back at Fort Bliss. In response, Piestewa lifted the plastic window that she had zipped down and showed him the bullet holes.

Nace didn’t think he could lead the convoy out of what he knew would be a withering attack once they headed back into Nasiriyah. Piestewa was the more experienced driver, so Nace asked whether she would switch places.

She shook her head. She knew her responsibility was to stay with her commander, even if it meant remaining in the last vehicle in the convoy – the most dangerous position in an attack. "I’m not getting out of this Humvee," she told Nace.

The officers climbed back in. "Take care, Pi," said Nace, slipping his vehicle into gear but terrified of what lay ahead.

"You, too," she told him. Nace was struck by how serene she sounded, as if she were just saying goodnight after another day of work back at Fort Bliss.

"She had this look on her face that was like: ‘Something is about to happen, but we’re going to be OK,’ " Nace recalls. "It made me feel at ease with myself. She gave me this calmness. If it wasn’t for her, I probably would have freaked out." Piestewa turned her Humvee around, took up position at the rear of the convoy and headed back toward the city.

Piestewa arrived at her new home in Fort Bliss, Texas, in October 2001. She was assigned to the 507th, where she was responsible for keeping track of supplies and performing other clerical work. She quickly developed a reputation for being efficient, friendly and quick to stand up for herself. "Pi was just her own person," recalls Spc. Shoshana Johnson, a company cook. "People would automatically assume she was Hispanic. She was like, ‘No, no. Piestewa is Hopi.’ She’d correct them in a heartbeat. She’d break it down to them."

A few months later, Piestewa got a roommate: a shy, petite eighteen-year-old named Jessica Lynch, from the hollows of West Virginia. The two could have come from different planets. Piestewa was a natural athlete; Lynch surprised her family just by completing basic training. Though they were the same height, Piestewa had an extra thirty pounds on the rail-like Lynch. Lynch spent hours getting her bangs and makeup just right and color-coordinating her outfit; Piestewa would throw on baggy jeans and a T-shirt three sizes too large. Lynch didn’t care about music; Piestewa, who loved Tupac, would crank the volume on her boombox and strut around the room as he rapped: "You either ride wit' us, or collide wit' us/It's as simple as that for me and my niggaz."

|

Despite their differences, or maybe because of them, Lynch and Piestewa became best friends. They quickly dispensed with first and last names, calling each other "roommate" or "roomie." They stayed up all night talking about boys and doing "girl things," dyeing each other’s hair and getting Lori out of her baggy jeans and into something more stylish. "They were like sisters," says Piestewa’s mother, Percy, who made the nine-hour drive to Fort Bliss with Lori’s kids as often as she could. "Jessi was teaching her how to be a girl again." When Piestewa and Lynch weren’t on duty, they drove Piestewa’s beloved charcoal-gray Mitsubishi Eclipse to the mall in El Paso and spent the day window shopping and going to movies. They didn’t usually watch war films, but Lynch remembers one they did see: Black Hawk Down, based on the 1993 firefight in Mogadishu, Somalia, that killed eighteen American soldiers and more than a thousand Somalis. "The film didn’t really bother us," Lynch says with a shrug. "We never actually thought we were going to Iraq. I mean, we’d always joke around and, you know, kid about it. But we never actually thought that we would end up in a combat zone." |

In January 2003, when the 507th got word it was to deploy to the Middle East, Piestewa was expected to remain at Fort Bliss. She had severely injured her shoulder in a training exercise and was recovering from surgery. But Piestewa knew her roommate was nervous about going into a war zone. And there were the other members of her unit to consider. So Piestewa decided to argue her way into deployment. Her kids were safe in Tuba City. The 507th was her family now, and it was in danger. She told her brother Wayland she had a feeling that Lynch – or someone else in the company – was going to get into trouble in Iraq. She wanted to be in a position to help.

Lynch told Piestewa it was OK, she didn’t have to go. But she had made up her mind.

"You have to – I have to," Piestewa told her roommate. She went to her superiors and lied about her shoulder, saying it had healed. She was returned to active duty.

On February 17th, as the 507th was leaving Fort Bliss, a reporter with local television station KFOX did a short interview with Piestewa. On tape, surrounded by her family, she appears relaxed about the deployment. "I’m ready to go," she says with a smile.

Nasiriyah. 23 March: roughly 0710 hours

As the convoy turned south into the city, the street itself seemed to explode. Heavy machine-gun fire erupted from all sides and AKs poured bullets down from the rooftops. Rocket-propelled grenades zeroed in on the large trucks. In seconds, the convoy disintegrated into a blur of chaos, dust, violence and adrenaline. The goal now was simply to survive, to get out of what the military aptly calls the "kill zone." The faster-moving vehicles raced ahead of the large trucks. Drivers mashed their gas pedals to the floor, but supply trucks aren’t built for speed. The Iraqis had made piles of debris in the streets, forcing the Americans to slalom around them while under the nonstop barrage. Tires were shot to tatters. Engines began to overheat.

Sgt. Donald Walters, who was trapped under fire when his truck was disabled, was taken prisoner. He was later executed – shot twice in the back. A soldier in the cab of one truck was struck by a bullet in the forehead and died instantly. Another had his arm shattered by a bullet. Another was hit in the hip. Another in the knee. The dust and flying sand jammed many M-16s, making it impossible to fight back.

Piestewa raced her Humvee through the city, steering around roadblocks, RPG and mortar strikes. It was as chaotic inside the vehicle as it was outside. Dowdy was firing his M-16 while shouting at the drivers they passed to "Hurry up, hurry up, go, go!" In back were two soldiers – Sgt. George Buggs and Spc. Edward Anguiano – picked up during the attack when their wrecker bogged down in the sand. They were shouting to each other as one fired a machine gun and the other tried to pick off attackers with his M-16. Jessica Lynch’s gun had jammed before she could get off a shot. She looked over at Piestewa and was surprised to see that her friend appeared calm – intent on what she was doing, but in control.

Up ahead, Spc. Edgar Hernandez was maneuvering an ungainly five-ton tractor-trailer through the ambush with Shoshana Johnson in the passenger seat. They crossed the Euphrates River into a more open area – only to find that the stretch of road was even more heavily fortified, lined with berms protecting scores of Iraqi soldiers and fedayeen militiamen. The gunfire intensified and so did the incoming RPGs and mortar shells. Hernandez ducked below the dashboard as bullets came through the window. He spotted too late a dump truck the Iraqis had parked in the middle of the road. He swerved to avoid a collision, and his truck jackknifed as it skidded to the right. It came to rest with the cab in the dirt and the trailer sticking into the road.

Piestewa’s Humvee was close behind, going at least forty-five miles per hour and weaving to escape gunfire. She had just turned to go around the disabled trailer when an RPG hit her front-left wheel well.

Inside the truck’s cab, Johnson was firing her M-16 when she felt a jolt. She and Hernandez had taken hits from RPGs, and Johnson’s first thought was that they’d been hit again. But the impact was stronger this time: The entire truck had been shoved forward. Hernandez looked out his window, back toward the trailer. He saw the wrecked Humvee sticking out from under the truck. The blast from the RPG had thrown the Humvee to the right, where it slid below the trailer, still traveling at a high rate of speed, and plowed into the truck’s massive hitch.

Percy Piestewa knew that the men in uniform knocking on the door weren’t bearing good news. But it could have been worse. Lori was missing in action. She could be alive. As word spread through Tuba City, family and clan members hurried over to be with the Piestewas. The vigil began. Every evening at six o’clock, as the sun was rising in Iraq, the Piestewas stood outside and, in traditional Hopi fashion, offered corn pollen and food. "We hoped that would give the girls the nourishment, the strength to endure," says Percy. "If they were in captivity and being tortured and stuff, that would give them the strength to deal with that."

There was encouraging news on April 1st. Jessica Lynch had been rescued from a hospital in Nasiriyah. But three days later, the men in uniform were back at the Piestewa’s door. The team that had retrieved Lynch had discovered a mass grave behind the hospital. One of the bodies had been positively identified as Lori’s. She had survived the crash but died at the hospital a short time later, lying in a bed next to Lynch, the roommate she had come to Iraq to protect. Piestewa was buried on Hopi land, out in the desert, in a cemetery reached by a rutted dirt road. On a recent day, her grave was covered with flowers, cards, a bottle of her favorite iced tea, a PayDay candy bar and a banner reading: "Forever Our Lady Warrior."

Piestewa’s family continues to appear at pro-military events, vocally supporting the troops that remain in Iraq. But as the fighting dragged on, their doubts and frustrations about the war itself began to slip out. In November, the Piestewas were the guests of honor at the convention of the National Congress of American Indians attended by 3,000 members, many of them veterans. During the opening session, Lori’s father and mother sat on the stage with her children, three-year-old Carla and five-year-old Brandon, as those in attendance rose and sang traditional songs in honor of Lori.

Then Terry Piestewa stood up. He thanked the audience for the tribute to his daughter – and called on all Indian soldiers to leave Iraq and come home. "It is not right for us Native Americans to be out there doing someone else’s job," he declared.

He received a standing ovation.

The following month, NBC aired a video showing Lori Piestewa in the hospital in Iraq, gravely wounded and in pain. Her family was furious at the network for what they saw as a ghoulish invasion of Lori’s last moments of life. They issued a scathing indictment of the media – and included some pointed anti-war criticisms of the Bush administration. It said in part: "Let us make sure that both President Bush, his father and each of his aides and advisers get a copy of Lori dying in agony so that they realize, from the comfort of their homes, that war should be the last option."

"We don’t want war," says Piestewa’s brother Wayland. "Unfortunately, we know that it’s one of the things that even our culture had to experience. But maybe we can change things next time. Maybe before we decide to go into another country, we can make sure we get all the facts. And let’s have those who are responsible for making that decision, let’s have them be truthful."

Even after Lori was buried, the circumstances surrounding her death remained sketchy. Every rumor was reported as fact, and her family didn’t know what to believe. They received reports of Lori fighting to the death, taking many Iraqis with her. "She drew her weapon and fought," Rick Renzi, an Arizona congressman, announced after one Army briefing. "It was her last stand."

It was the kind of image that would make many military families proud: the heroic warrior, guns blazing, fighting to the end. But when Terry Piestewa finally learned the truth about his daughter’s death, he was relieved. Lori hadn’t fired a shot. All she was doing was driving, trying to get the people she cared about to safety.

"We’re very satisfied she went the Hopi way," her father says, smiling. "She didn’t inflict any harm on anybody."

© Osha Gray Davidson, 2004 Rolling Stone, 27 May 2004.

Return to: Native American Church